Timber Framed Structures: Design & History of Building Technology

- Sean Kamana

- Apr 5, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: May 21, 2025

April 5th, 2025

With reference to A Building History of New England by James Garvin

and Timber Design & Construction Sourcebook by K. Goetz, D. Hoor, K Moehler & J. Natterer

In the heartland of the earliest communities of Northern New England there are whispers of past lives lost and succeeded throughout the wooded hillsides. Just as the earliest continental practices of law, religious freedom and community were formed in the vast expansive unknown of the White Mountains, the wooded hut emerged as the most practical, establishing technology to found societies. Trees were fell with haste, hewn and joined. Timber framing was imported to New England from the golden ages of European timber carpentry.

The engineering of old houses and structures is often ancient and intuitive, resolved over many generations. Even when we look now at many engineering problems when analyzing timber structures, it becomes less significant to consider the tensile or compressive force on timber beams and rafters and more to do with the overall strength of wood and the intuitive nature of perceiving which timbers have proper grain and straightness. Wood is much less strong today than it may have been during the best old age growth years in North America.

There is a powerful mythos in American history and culture of the Log Cabin. It represents a homeliness and salt of the earth. Many past presidential candidates such as Lincoln, Taylor Garfield and Grant were raised in one. Early log cabins settled in New England in the late 17th to the end of the 18th century were typically temporary structures to give families lodging until more permanent framed structures could be erected providing comfortable housing for settlers. The log cabin remains an icon of an American pioneering attitude and frontier virtues. Many patrons have coopted the log/timber cabin aesthetic for their own summer homes and camps to this day. Many preservationist initiatives remain to preserve this timeless and familiar method of building.

Richard Jackson House - Portsmouth 1664 (link)

The first log cabin in North America was recorded to have been built in Portsmouth, NH in 1659. The longest still standing wood framed house, the Jackson House is also in Portsmouth NH, built in 1664. By the 18th century many carpenters and craftsman were either hewing or hand sawing timber frames and transporting or selling these frames up and down the eastern seaboard and beyond. For example, from 1771 until the Revolutionary war broke out, carpenters on the borders of Maine and New Hampshire reportedly shipped nearly 147 workmanlike timber frames as far as the East Indies. Timber framing and the construction of log cabins has been a foundling industry supporting the communities physically and economically since the first days of American colonialist.

Much of timber framing knowledge was of course imported to North America by British, Dutch, French and other settlers. Despite this, the availability of more old growth forests and larger wood timbers as well as the development of the water powered circular sawmill provided carpenters and craftsman opportunity to cut new kinds of framing members and employ new techniques for erecting homes and commercial structures alike. These techniques and industrial innovations have largely remained significant in the practice of building homes still today.

By the 1830s the scribe rule of crafting timber joints gave way to the square rule which led to greater standardization of parts. The scribe rule was a way of laying out a frame on the ground and scribing all the joints with numerical values to then be reassembled when the frame was erected. The notable inaccuracy of these frames and dissimilarity of comparable joints was a result of the hewn nature of timbers and their relative irregularity. The square rule introduced greater care in the drafting of framing plans.

With this improved process, timbers of varying sizes and intended uses could be cut and crafted at different sites and transported individually. This allowed different joints and brackets or rafters to be more interchangeable throughout the building process. The main constraint toward the development of this process was that hewn timbers may not be interchanged due to varying dimensional differences of wood. The square rule allowed for a standardized joint which meant that all joints of the same type bore identical relationships to one another. The square rule bears its name notably from the use of a framing square to lay out joints and connections as well as the fact that after 1830 most framing members were mill sawn rather than hewn and could be relied upon by the builder to be perfectly square in section.

With the wide spread development of more and more available mill sawn timbers, the conventional nature of 2" timber common rafters and joists became an increasingly cost effective and speedy way to manufacture and install wooden frames in structures. Standardization and the increasingly prevalent industrialized means of manufacturing during this time shifted concerns of carpenters from traditional practices of their trade to a new conventional method of craft. Even in name, "clapboard" originated from the Dutch word "klappen," which means "to split". Historically, clapboards were hand-split from logs, producing boards with one thicker edge that overlapped the next, creating a weatherproof barrier on buildings. This splitting process, known as "riving," was a key characteristic of early clapboards, and the term likely reflects this method of production

With greater standardization and industrialization came the development of not only water and steam powered cutting mills but also plane shops which could produce many more perfectly flat boards. As homes transitioned away from the vernacular and traditionally crafted timber post and beam, plank houses became more widespread through the late 18th century. As a result of these developments and the insistence on wood as a building material for continental builders, the resurgence of classical moulding profiles flourished in the Georgian style of architecture in New England. The industrialization of sawmills and planing provided the infrastructure necessary to deploy intricate moulding knives and efficiently cut curved wooden profiles from stock boards. More elaborate designs for more wealthy clients necessitated a builders guidebook to maintain the ordered and pleasantly evocative nature of a curves on buildings. These early guidebooks set the precedent for nearly all the seminal colonial and classical applications of profiled eaves, porticos, chimney breasts and trim in many historical homes throughout New England. Despite the possibility of builders being uneducated in the orders and rigor of a classically informed school of design, these guidebooks made classical representations of architectural detailing available to even the most green carpenters' apprentice.

James Garvin says in his book: "The act of impressing a curve into a flat surface immediately evokes a response in the human eye that cannot be explained by rational grounds alone. The play of light and shade across a regularly curved surface is naturally pleasing, and much thought and artistic impulse have been devoted over the centuries to the subtleties of such surfaces."

(page 37 The Evolution of Building Technology from "A Building History of Northern New England" 2001 J Garvin)

Understanding the evolution of early American building practices can inform future developments toward or away from a conventional attitude of architectural design. With increased technological advancements to the manufacture and installation of timber members much of these early practices have rightly fallen from the fashion due to the inefficiencies of producing such frames. Despite this, the northern New England attitude toward vernacular architectural designs remains a practical and engaging building method. Many architects have continued to employ even the most basic and economical principles of these designs to find they are very successful in replicating them for clients of all backgrounds and tastes. Traditional heavy timber framing with oak, hemlock and pine remains an iconic and vernacular style of building throughout the northeast, much of the American and Canadian west, as well as of course throughout Europe still today.

In contemporary practice, the innovation in wall technologies has promoted a resurgence of highly engineered wall assemblies that continue the the traditions of the square rule by relying heavily on precise framing and shop drawing plans. Most notably the structurally insulated panel (SIP) is a thermal barrier that stands up to modern energy standards now that homes are heated and cooled with mechanical systems. These panels have innovated the building process. Specifically the sequencing of construction, in that they provide the ultimate standardization of parts. The same way that early settlers of New England would arrange their frames on the ground and ship them anywhere in the world, manufacturers today rely on designs and drawings provided by the architect to build and install these extremely energy efficient systems. After a timber frame is fully installed and joined, the builder can block out cavities at the tops of wall plates and ridges and use a crane or boom (typically already available on the job site with the timber frame) to lift and fasten these panels into place with structural screws. This creates a true continuous thermal barrier around the entire home and ensuring a very tightly sealed home regardless of the season.

Notable other projects of interest:

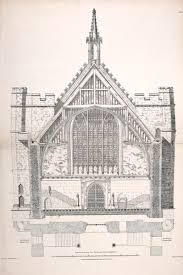

Westminster Hall:

Built in 1097-1099 London England by William Rufus.

1390: Remodeled by King Richard II, who raised and reinforced the walls and constructed the hammer-beam roof.

1883: J.L. Pearson rebuilt the flying buttresses on the west side after extensive fire damage.

Mystic Seaport:

Thompson Exhibition Building Mystic Seaport is the oldest and most popular tourist destination in Connecticut. It is a living history maritime museum that celebrates New England’s nineteenth century whaling and shipbuilding industries. The museum decided to build a new visitor’s center and exhibition building to anchor the North end of its museum campus. The focal architectural feature of the building is its glulam timber roof structure. Upon entering the building, your eye can’t help but being drawn to the majestic curved timbers, but what is most notable about the timber roof structure is what you don’t see. There are no clunky steel gusset plates connecting timbers, instead you see elegant scarf joints inspired by traditional shipbuilding joinery.

Other sources: